Article by Noel Pearson, courtesy of The Australian

19.07.2025

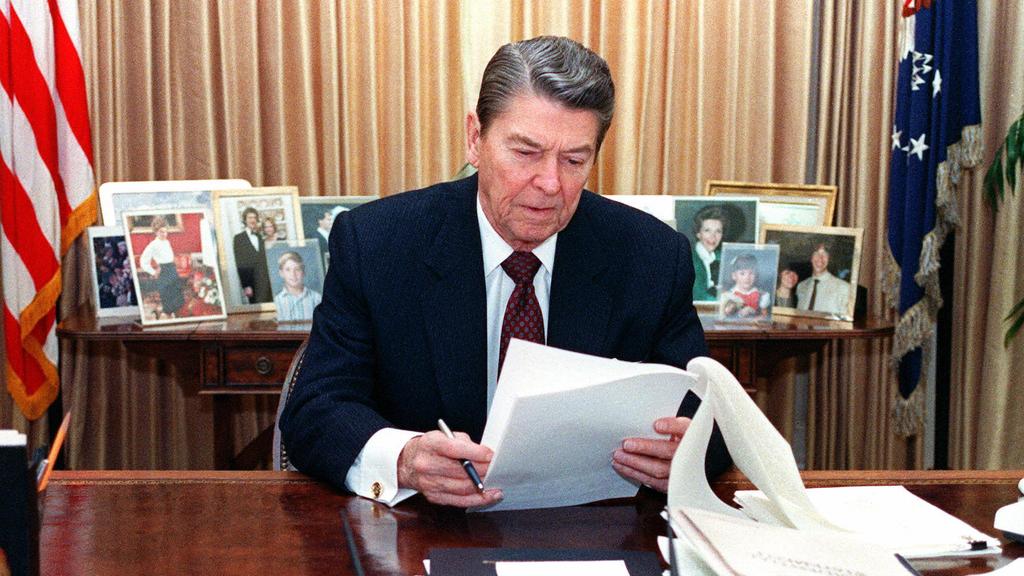

“Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” So said president Ronald Reagan, famously or infamously depending on whether one is a believer in big government or not.

After my experience of governments for more almost four decades, having always tried to work with government from the non-government side, I have to confess to being an unbeliever.

But not for the ideological reasons that informed Reagan’s view; rather because of my experience of the incompetence of governments and their chronic inability to deliver. This incompetence has grown over these decades. Governments have even less capacity to deliver to the public than ever.

When Jim Chalmers convenes his roundtable on national productivity next month the leviathan in the room will be the question of the sheer competence of governments. What a drag on productivity this incompetence represents. Governments can’t organise a proverbial night of debauchery in Kings Cross with a fistful of dollars.

Who believes the latest programs announced to combat the epidemic of the killing of women, or the building of thousands of new homes, or delivering nuclear-powered submarines, or closing the gap on Indigenous disadvantage will work? Will they produce the results that are intended?

It is my experience that, whatever complaints Australians have about governments, we are still great believers in government. This is bipartisan. There are a few libertarians, but most Australians are believers in government. I have never discerned any great difference between Labor and the Liberal National parties in terms of their belief in the role and efficacy of governments.

The conservatives talk about freedom of the individual and the importance of the private sphere, but they still believe in the power and primacy of government no different to the Labor mob.

One of the five pillars of Paul Kelly’s Australian Settlement thesis in his 1994 book The End of Certainty explains this belief in government: the pillar of state paternalism. We are not, first and foremost, like the Americans, rugged individualists. We are subscribers to the collective guarantee that government must and can look after all of us, in our every respect.

As someone preferring the Australian rather than the American disposition towards government, I am nevertheless challenged by the fact of governmental incompetence. I am more cynical than the average because of my experiences at the coalface of the governmental interface with the non-government sector.

There is first the Westminster system of ministerial leadership of the arms of government. It contrasts with the American system whereby cabinet secretaries are chosen by the President and can come from outside government, or serving or former members of congress or state legislatures. The American system must be better.

For every great minister who serves within our system, there are a dozen ordinary ones, some very ordinary indeed. If only I had a dollar for every minister for education, health, housing, families, child protection, Indigenous affairs, regional development who hardly had a clue as to what they wanted to do with their portfolio and how to do it. If you asked: so what was achieved in the three or six years you held this great power and responsibility? What were the reforms you secured and what social progress resulted? The answers are dismal.

I am often approached with great zeal and passion by former ministers with convictions about what must now be done, only to wonder: so why didn’t this happen when you held the reins?

There is far too much talent, experience and leadership ability outside of political parties that is lost to our system by making the administration of government the sole domain of professional politicians.

The policy competence of governments is desultory. Australian governments don’t do policy well. The country doesn’t have the technocratic capacity of the Singapore government. Take education: if Singapore’s education department ran the Australian system there would be more equity and more excellence than is the case at the moment. It is not hidebound by ideological arguments like we are, it is always searching for what works.

Both in terms of the quality of policy production and implementation, I don’t think there’s any doubt that there has been a deterioration in the ability and performance of government. Governments that built great Australian institutions such as Telecom, Qantas and Australia Post, universities, public hospitals, highways and all kinds of infrastructure are now assumed to be completely incapable of doing such things, which should be left to the private sector. Few would disagree that governments are now incapable of doing such things, but they once were.

Of course, privatisation brought with it an ideological panoply about the incompetence of government that was self-serving to those who urged privatisation and historically wrong but is now correct because of the decades of degradation of governmental personnel and capabilities. Governments actually are less competent than they were.

Governments routinely outsource their functions in policy review, analysis, evaluation and planning to private sector consulting firms. This is a massive industry. Functions that were in-house in the bureaucracy are now outsourced. Not only because of the greater expertise and ability available from consulting firms – which is by no means universal or always the case – but also because outsourcing becomes a convenient method of political risk management.

Better to get the consultant to develop the plan that might upset stakeholders than to do it in-house. Outsourcing policy has become the favoured method for bureaucratic and ministerial backside covering.

The federal government’s curtailing of consulting services is welcome, but whether the in-house competency will improve is another question.

Micro-economic reforms since the 1990s produced a revolution in the role of government. That it has produced a degradation in the competence of government is something we must now confront if we are to talk honestly about productivity.

Outsourced government services have not equated to more productive government services. While administrative processes may be less lugubrious than they used to be and competitive tendering may have produced some savings, the question remains: do we have better social, economic and cultural results? Are poverty and disadvantage turning around since we outsourced human services? Are our schools better? Where are the improved results?

The plain feeling that government is not delivering pervades Western democracies, not least in the US under President Donald Trump. As wrongheaded as Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency was in terms of its brutal and ill-fated solution, it spoke to a real problem. Government is inefficient and incompetent, and urgently needs reforms.

It’s not just savings, it’s the return on investment that must be confronted by the Treasurer’s roundtable on productivity in August. The predicament of the bottom million in Australia, of which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people comprise a sizeable proportion of the numbers, must by the focus of productivity. It’s the wastage of lives and not just the wastage of money that is at stake here.