22 June 2015

Wendy Frew

BBC News

Forced to rethink its reliance on a mining industry now in decline, Australia is looking north for growth and opportunities. But some worry the vision could be a mirage.

When Prime Minister Tony Abbott last week released a white paper with proposals to develop the 3m sq km (1.86m sq miles) that make up the northern part of the continent, Australians could have been forgiven for thinking they had heard it all before.

The White Paper, Developing Northern Australia: Our North, Our Future, aims to tap the potential of the country’s least developed region, which stretches from northern Western Australia, through the “Top End” of the Northern Territory and into Queensland.

It is a massive area that includes natural wonders such as the Great Barrier Reef and Kakadu National Park, and tourism havens like Cable Beach in Western Australia. But it is home to only around one million of Australia’s population of 23.4 million.

Mr Abbott believes “a strong north means a strong nation,” which is why the White Paper delivers an initial investment of A$1.2bn ($932m, £587m).

“The White Paper includes measures to unlock the north’s potential across six key areas,” says Mr Abbott:

- Simpler land arrangements to support investment

- Developing the north’s water resources

- Growing the north as a business, trade and investment gateway

- Investing in infrastructure to lower business and household costs

- Reducing barriers to employing people

- Improving governance

Observers note it is not the first time Australia has looked north for economic salvation, while critics warn of a range of reasons why it will not be easy to tame the country’s last frontier.

Analysing the Coalition’s initial 2030 plan for developing Northern Australia, released ahead of the 2013 election, academics from the Charles Darwin University said the idea was akin to making a sequel for an old cinema classic.

Tony Abbott isn’t the country’s first prime minister to devise a strategy for developing Northern Australia.

- In 1926, Stanley Bruce said northern Australian development was “of immense strategic importance”

- In 1944, John Curtin said it was “essential to future security”

- And in 1969, Gough Whitlam said it was “necessary and urgent”

Source: Charles Darwin University

“It evokes familiarity and the repackaging of tested and yet-to-be tested concepts,” say academics Sharon Bell, Andrew Campbell and Steve Larkin.

“It also inspires hope that a fresh narrative and some special effects will deliver greater box-office success than last time,” they wrote for The Conversation website, noting that the first Commonwealth parliamentary inquiry into the development of northern Australia was held in 1912, a little over a decade after federation.

Many other plans followed and failed.

But that doesn’t mean the north can’t be developed. The team at Charles Darwin says Northern Australia, “especially in the larger cities, is already experiencing economic and demographic transformation”.

“Energy, business, research, education, culture and health provision are undergoing innovative and often sector-leading changes,” they say, adding that there are plenty of opportunities to build on existing trade, cultural and investment links with the Asia-Pacific region.

But there are hurdles, too.

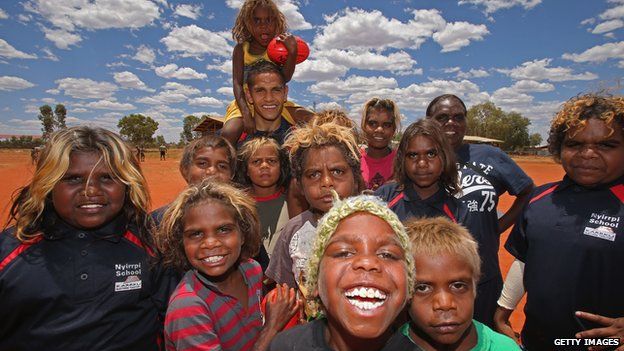

An influential Aboriginal leader from Cape York in the far north of Queensland, Noel Pearson, warned on Friday the government needs to consult indigenous Australians, who make up a large percentage of the northern population and have native title over a lot of land.

Mr Pearson has often clashed with environmentalist groups because he has championed greater development in northern Australia.

However, he is concerned developers will try to sideline indigenous interests in the region, leaving local people with only the “scraps from the table”.

“Our concern is that governments, including the Commonwealth, see this as a Trojan horse to undermine Mabo,” he said, referring to a landmark 1992 court ruling recognising native title in Australia.

Agricultural development has attracted the most attention over the years.

In the 1950s, Australia tried to transform its northern “wasteland” into productive territory by damming Western Australia’s Ord River and creating a lake big enough to hold nine times the amount of water in Sydney Harbour.

The plan was to irrigate thousands of hectares of land and grow crops such as sugarcane, cotton and fruit. But a combination of intense dry and wet seasons every year, plus pests, tropical diseases and infertile soils soon turned the Ord River project into a white elephant that didn’t make a financial return for about 50 years.

In 2006, as southern farmers faced crippling drought, federal politicians once again started talking about moving farmers away from the cracked river beds of the Murray-Darling basin to the rain-soaked north. It was another plan that didn’t get much traction.

Northern Australia’s farming failures include

- The Northern Territory’s Humpty Doo rice experiment of the 1950s

- The Camballin rice and cotton venture in the Kimberley, Western Australia, abandoned in the 1980s

- The Northern Territory’s agricultural development marketing authority farms of the early 1980s

Mr Abbott’s blueprint is much broader than agriculture, encompassing investment in transport and changes to regulations the government hopes will open doors to local and foreign investors.

The Northern Territory Livestock Exporters Association was one group pleased to see extra funding for roads.

“It is an outstanding initiative and we applaud that,” the association’s chairman Andrew Gray told the ABC.

“The pastoral industry has been crippled by poor roads. We have heavy rain during our wet season. Roads become impassable for passenger vehicles, let alone for the transport of livestock.”

The National Farmers’ Federation also welcomed the strategy, arguing that “a strong agricultural sector is vital to ensuring development in Northern Australia”.

Environmentalists were less happy, especially because the funding eclipsed any money set aside for the Great Barrier Reef.

The Reef is the North’s most important natural asset, generating A$6bn a year and supporting nearly 70,000 jobs, says WWF-Australia Chief Executive Dermot O’Gorman.

“We should prioritise investments in assets which are proven economic performers – the Great Barrier Reef is the real economic powerhouse of the north,” says Mr O’Gorman.

The government’s white paper outlines a long list of issues that will be tackled to make private investment in the region more attractive. It hopes to kick start interest later this year with an investment forum held in the nation’s most northern city, Darwin.

Courtesy of BBC News