Article by John Kehoe, courtesy of The Australian

23.07.2025

The federal and state government spending splurge has hit the highest level since the end of World War II, due to a massive ramp-up in outlays on disability support, aged care and childcare.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme is the chief culprit, accounting for $52 billion in costs and making Australia among the biggest government spenders on disability in the world.

More than half of voters now rely on governments for most of their income, through public-sector wages, welfare benefits or subsidies according to a new report by the Centre for Independent Studies, a right-of-centre liberal think tank.

“This dependence poses a formidable opposition for any politician trying to curb the growth in public expenditure,” CIS senior fellow Robert Carling said.

“A culture of dependency and entitlement has taken root in the population and political behaviour has become only too willing to accommodate and encourage it in a feedback loop.”

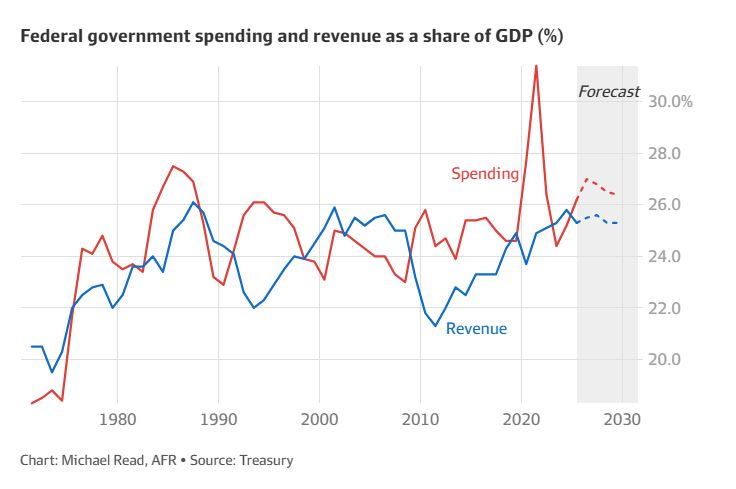

Federal Treasury warned in a post-election briefing to Treasurer Jim Chalmers that government spending must be cut and taxes increased to put the federal budget on a sustainable footing.

Chalmers will host a three-day Economic Reform Roundtable in August to discuss ways to increase productivity and make the budget more sustainable, including potential changes to the tax system.

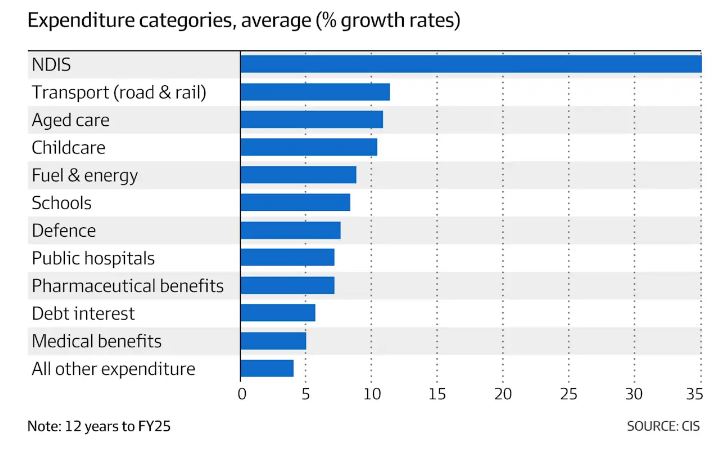

Budget deficits and rising public debt are tipped to increase interest payments by governments by almost 10 per cent a year for the next decade, as governments face higher borrowing costs than the ultra-low interest rates during the pandemic, according to the CIS’s report, Leviathan on the Rampage.

Total federal and state government spending has surged to a post-war high of 39 per cent of GDP, up from about 34-35 per cent before the 2008 global financial crisis.

Carling said the current spending splurge might have only been equalled more recently than WWII in the 1980s before the Hawke-Keating Labor government cut spending.

A dozen federal social spending, care economy and defence programs, along with public debt interest, have averaged growth of almost 10 per cent a year since 2012-13, lifting their share of the budget from around 35 per cent of expenditure to almost 50 per cent.

Carling, a former federal and NSW Treasury official, said the $52 billion NDIS was the chief culprit for spending blowouts.

“The National Disability Insurance Scheme has repeatedly exceeded cost estimates by a wide margin and has done more than any other program to drive government spending growth,” he said.

Australia now outlays more than $90 billion a year (more than 3 per cent of GDP) for the NDIS, disability support pensions and carer payments.

Spending on disability exceeds the individual budgets for the age pension, defence, aged care and Medicare.

Labor’s planned reforms to the NDIS are slipping behind, as Canberra struggles to get the states to agree to take on more responsibility for children with developmental delays in the health and education systems.

Childcare subsidies have already more than doubled from $6 billion in 2018 to $14 billion a year, with little obvious benefits for women’s workforce participation, out-of-pocket fees, or better outcomes for children.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has laid out ambitions to deliver universal childcare, which could add up to a further $13 billion a year to the cost, according to the Productivity Commission.

During the election campaign, Albanese offered more free doctor visits, free TAFE, and free lenders’ mortgage insurance for first home buyers.

Moreover, Carling said so-called “off-budget investments” – such as the Albanese government reducing student loans and spending more on green energy funds – added $104 billion in hidden spending over five years.

“The growth of government spending remains a serious economic

concern because of what it means for persistent budget deficits, rising public debt and taxation, weak productivity growth and the societal consequences of a deepening dependency on government,” he said.

Four in five jobs created in the past two years have been in the non-market sector, which are occupations in industries heavily influenced by government spending and regulation.

Minutes from the Reserve Bank of Australia’s monetary policy board meeting released on Tuesday noted a decline in public demand (government spending) in the March quarter was expected to be temporary.

“Recent government budgets remained broadly consistent with the staff’s expectations for growth in public demand in the May forecasts,” the RBA noted.

“Employment growth in the non-market sector – which includes healthcare, education and public administration – had started to ease in early 2025 from a rapid pace, while employment growth in the market sector had picked up a little in year-ended terms.”

The boom in government-funded jobs in care and bureaucracy is dragging down labour productivity, the Department of Employment has warned the Albanese government, in frank advice before Chalmers’ economic roundtable.