Article by Patrick Commins courtesy of the Australian.

Australians are less likely to start companies or switch jobs than in the past, reflecting a drop in economic dynamism over the past decade that has underpinned the nation’s worst productivity performance in history.

The increasing concentration of power among a dwindling number of big firms in key industries – “from banks, to beer, to baby food” – has also robbed the economy of vitality, Competition Minister Andrew Leigh told The Australian.

“Traditionally, one of the best ways we have boosted productivity is through new start-ups, people moving to new jobs, and through insurgent companies challenging incumbents,” Dr Leigh said.

“That’s driven a lot of growth historically. But that process seems to have slowed,” he said.

In a speech to the ANU on Thursday that will put competition at the heart of the productivity challenge, Dr Leigh will say “slower productivity growth means lower real wages and less buying power for households”.

“It constrains the ability of the budget to build infrastructure and help poor people here and overseas. Whether your priority is paying down debt or boosting teacher quality, you should be worried about the drop in productivity,” he will say.

Dr Leigh will also say there was evidence the largest firms have increased their market share, with the lack of competition giving them the power to steadily increase mark-ups on their products. “All this suggests that the Australian economy has become less competitive,” he will say.

Former ACCC boss Rod Sims, now a public policy and anti-trust professor at ANU, told The Australian that merger laws needed to be amended to make it easier for the regulator to prevent acquisitions that substantially reduced competition.

Professor Sims said oligopolies tended to stifle innovation – a prime driver of productivity – as dominant firms were unwilling to cannibalise their existing products and services, even as they undermined the ability of new competitors in their industry. “These issues are important for the jobs and skills summit because there is evidence that concentrated markets do hold back wages,” he said.

Dr Leigh will say he will be relying on work done by the ACCC’s digital platforms inquiry, the Productivity Commission’s five-yearly report early next year, and the next intergenerational report – due to be delivered in the next two years – to shape a policy agenda to tackle declining competition.

“Competition policy should be one of the factors that we consider when implementing regulation, given regulatory costs for new businesses are larger relative to their size,” he will say.

“Linking workers with new jobs faster will also encourage competition and dynamism, which we recognise through our jobs summit and the white paper that will follow. We also help competition when we encourage investors to back productive new opportunities instead of parking wealth in existing assets.”

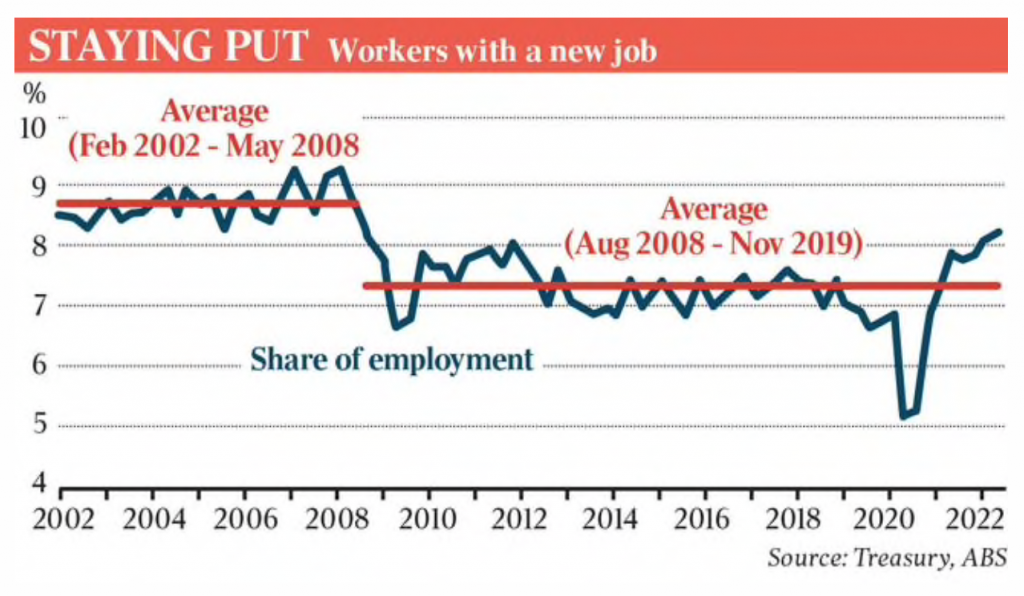

Dr Leigh on Thursday will provide several examples of declining dynamism, based on his own research. The share of workers who started a new job has dropped from 8.7 per cent in the period from February 2002 to May 2008, to 7.3 per cent in the period from August 2008 to November 2019, he will say.

The rate of new companies as a proportion of total businesses dropped from 13 per cent in 2005-06, to 11 per cent in 2018-19. In the same period, the business failure rate fell from 10 per cent to 8 per cent.