Article by Sarah Elks courtesy of the West Australian.

Mines, gas projects, farms and other industries in Australia’s second-biggest resources market and third-biggest agriculture sector could be shut down by a bureaucrat’s decision, under secret legislation drafted by the Queensland Environment Department.

Industry stakeholders were forced to sign an unprecedented confidentiality deed by the department’s strategic policy team – led by former Wilderness Society campaign manager and anti-mining activist Tim Seelig – gagging them before they were allowed to see proposed Environmental Protection and Other Legislation Act amendments.

Several high-level sources said the draft bill as circulated would give a bureaucrat, likely the Environment Department’s director-general, the power to wind back retrospectively existing environmental approvals, licences, and permits to slash production capacity.

That means farms could be told they need to cut the number of livestock they can have, mines could be told to dig up less coal and gasfields could be instructed to extract less gas, in defiance of existing environmental authorities awarded by the department.

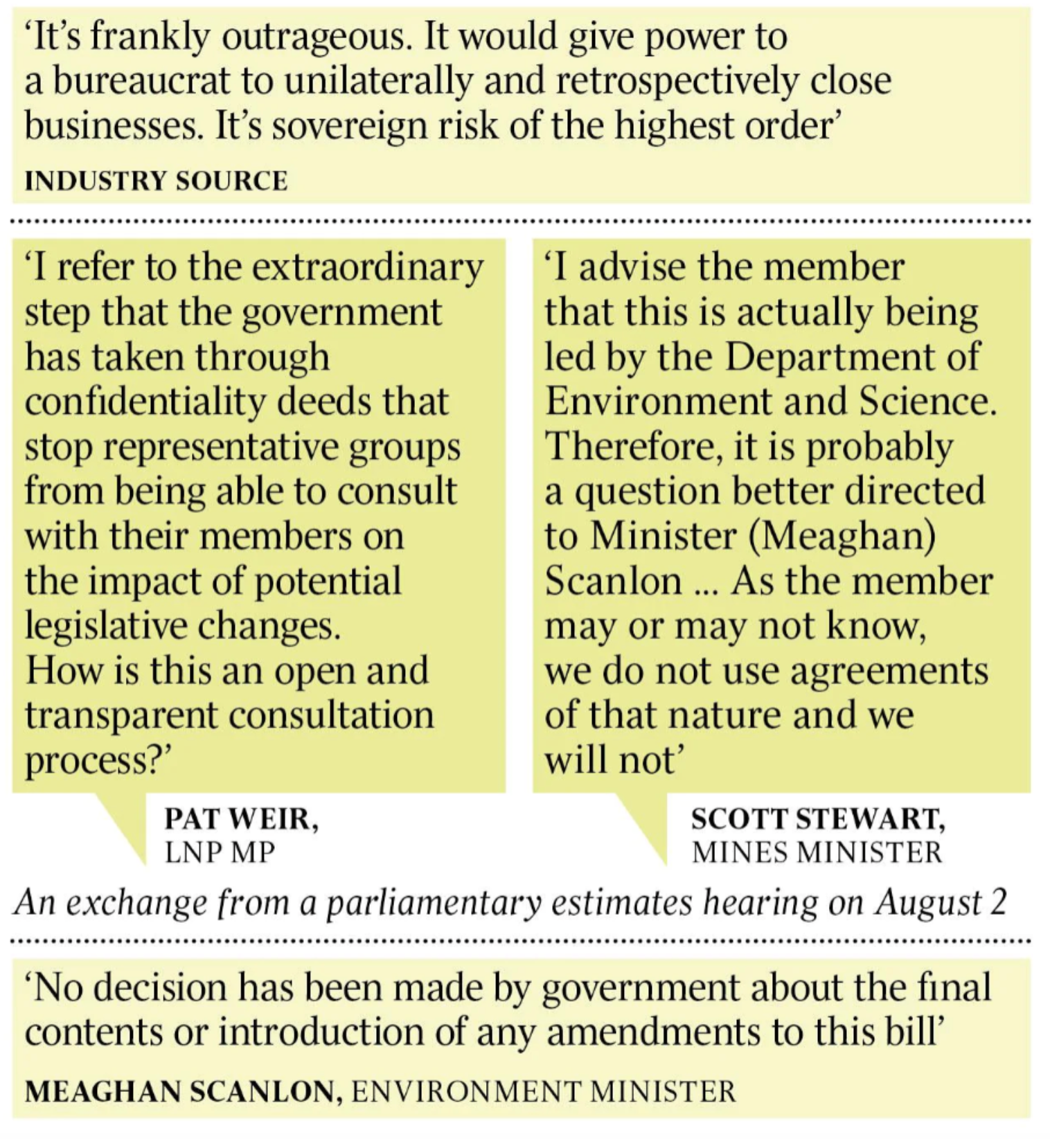

An industry source said: “It’s frankly outrageous. It would give power to a bureaucrat to unilaterally and retrospectively close businesses. It’s sovereign risk of the highest order.”

The legislation, if passed in the original form, could threaten Queensland’s $90bn resources and $14.5bn agriculture industries, as well as aquaculture and other sectors. There is concern it would also increase the amount of red tape involved in new environmental approvals, such as environmental impact statements.

After The Australian asked about the plan on Monday, a spokesman indicated the Environment Department had changed its mind about pursuing retrospective powers. “DES (the Department of Environment and Science) is not considering any amendments to legislation that would apply retrospectively,” the spokesman said.

But fresh amendments to the EPOLA Act have not yet been drafted, and industry sources say they are still concerned about the department’s plans and unsure how its new promise to not introduce retrospective powers would apply to existing projects.

“We’ll believe it when we see it in writing,” an industry source said. “We don’t know whether production limits would apply to existing projects. There’s still a question about what the department means by what’s retrospective or not.

“From an industry perspective, a project that’s been built and established for decades, has got to have a reasonable degree of certainty about the future. We don’t have that.”

The Environment Department spokesman did not say what the environmental justification was for the new measures, and said there had been informal and formal consultation, engagement events, and individual stakeholder discussions for a year. “DES will take into account all stakeholder feedback in finalising any proposed legislative amendments,” he said.

Environment Minister Meaghan Scanlon said: “No decision has been made by government about the final contents or introduction of any amendments to this bill”. Ms Scanlon said she expected her department to consult all stakeholders, as it had done since August last year.

Ms Scanlon’s spokesman said confidentiality deeds had been used because of the “preliminary nature of the draft” legislation.

Association of Mining and Exploration Companies chief executive Warren Pearce said the “continued behaviour of secrecy from government is highly concerning” and the process run by the Environment Department was “extremely disappointing”.

Industry sources were on Monday surprised the department had said it was no longer pursuing the retrospective elements of the bill, which had been the subject of significant uproar during the secret consultation.

Queensland Resources Council chief executive Ian Macfarlane attacked the use of confidentiality deeds, saying they hindered the ability of peak bodies to consult properly with their members about the exposure bill.

“It’s not transparent governance,” Mr Macfarlane said. “It’s very opaque, and it increases the likelihood of bad outcomes.”

The confidentiality deed warned industry groups it conferred “unlimited liability in favour of the government” to mete out unspecified punishment if the draft exposure bill was leaked and caused damage to the Palaszczuk administration. The deed was eventually altered to allow organisations to consult with some of their own members about the proposal.

Mines Minister Scott Stewart is understood to be furious at his cabinet colleague Ms Scanlon’s department’s use of the deeds to silence industry during consultation. During recent estimates hearings, Mr Stewart was asked about the use of the agreements to consult about the EPOLA Act.

“This is directly the responsibility of Minister Scanlon and the Department of Environment and Science … we do not use agreements of that nature and we will not,” Mr Stewart said.

AgForce chief Mike Guerin said although the practice of using confidentiality agreements was unusual, he thought it appropriate. “The whole area’s one of the most sensitive,” he said.